Windom, Texas stands tall on the highest point in the county. Defined by the water tower and the grain elevators, it can be seen from miles away. I cannot tell you when that water tower and those grain elevators became synonymous with “home” - they simply are, and have been from my earliest memories. This is the story of the wheat harvest of 2018, told from the perspective of my little town on the prairie and from my experience as a daughter of the land.

With the exception of the historic family photos, the black and white images in this essay were taken with home made pinhole cameras made from coffee cans, oatmeal boxes, and cookie tins. They were made on direct positive photographic paper and were developed in my improvised dark room using a concoction of instant coffee, washing soda, and vitamin C. The process was chosen deliberately to be as low-tech as possible. The color photos that I’ve included, primarily to provide some context for the more conceptual images of the harvest activity itself, were taken with my iPhone - a massive computer tucked into my back pocket. I have used these primitive photographic methods along side the most modern as a means of contrasting my perspective growing up on a small family farm of the 1950’s and 60’s with the large, high-tech, commercial farming of today. The work is a testament to the overwhelming rate of change that has occurred in my lifetime and a celebration of what endures. It is a homage to the farmers from which I sprang and to the men and women who feed us today.

My entry into the farming world, circa 1953.

Farming technology at the time. My grandfather is driving the tractor. When he was born in 1891, radio was not yet a thing and the gas-powered automobile was a rarity only 6 years old. When my father died in 1981, he was still using that old tractor.

I was about 14 when this old truck was replaced. It had been used to bring our harvests to market for years.

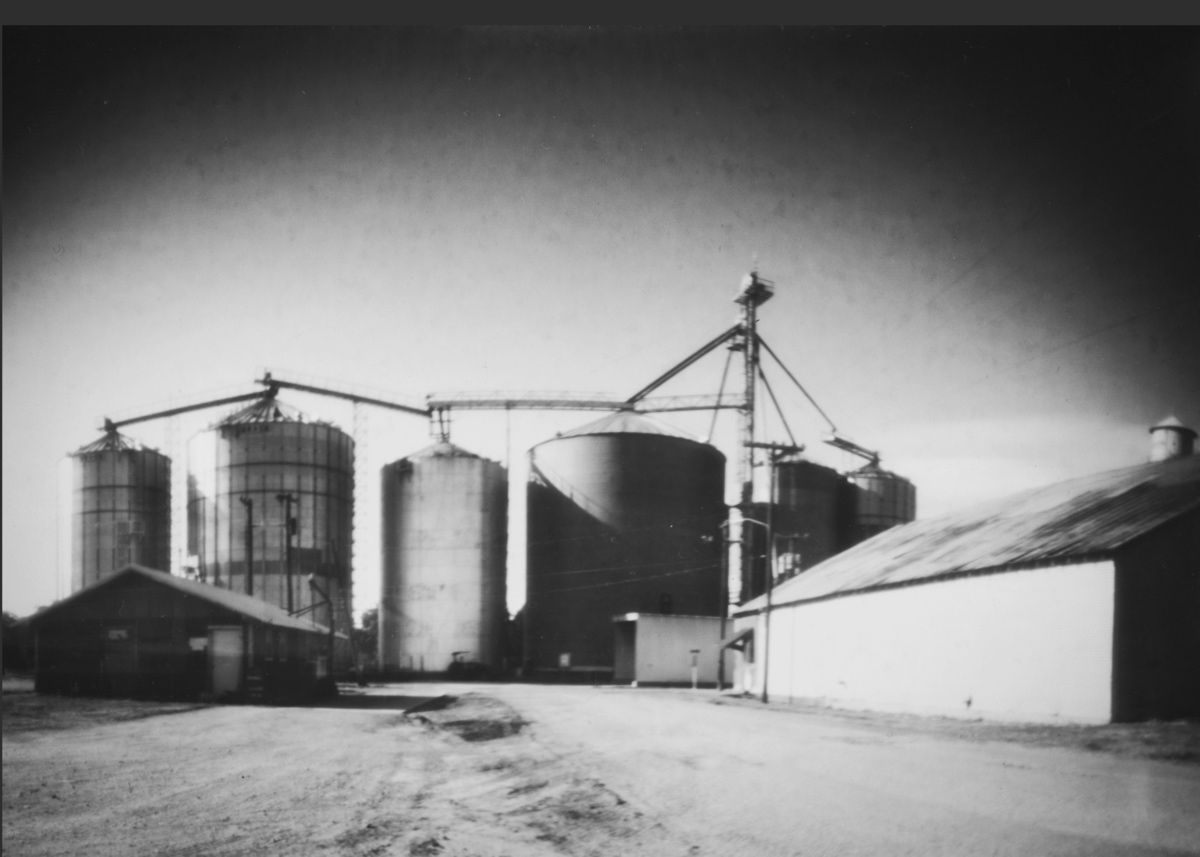

Windom has always been an agricultural community. We once had a school, five churches, two grocery stores, a service station, a bank, the mill, a blacksmith shop, a beauty shop, and a cotton gin. Today the mill stands exactly where it did when my Dad, my brother, and I would bring our grain to town in our old pickup truck equipped with homemade sideboards. It is one of the few local businesses that survived the years and the shift of most economic activity to other, larger towns. We have a popular weekend restaurant where one of the grocery stores used to be, some of our churches still thrive, and the annual ice cream social and fireworks display on the 4th of July always draws a crowd to our community park.

Most days of the year, however, our town is a very quiet place. That is, until the harvest.

In the beginning, the trucks arrive by ones and twos. Big semi-tractor trailers, a single one of them is probably worth more than our entire farm was worth back in the day, and they are soon arriving in droves. As the intensity of the harvest grows, trucks stack up, early in the morning, around the pecan tree in the lot waiting to be weighed. Then they queue along the main street waiting for the signal to move up to be unloaded. Arriving, queuing, moving up, weighing, queuing and moving up again, unloading, departing to collect another load, the mill becomes a hive of activity from daylight to dark. Trucks arrive before the mill opens, and drivers arriving late in the day sometimes spend the night in their trucks in the mill yard. For the workers at the mill, it is hot, dusty, noisy, exhausting work that will not let up for the better part of a month. .

I knew from the first that I wanted to use pinhole photography for this project even though I had little experience with it. Making the cameras myself was also part of my vision - using my own hands to make my tools gave me a sense of connection to my parents and grandparents for whom scrappy self-reliance was an everyday survival skill. A learning curve was inevitable, and I won't recount the many failures along the way. I spent weeks in the spring getting ready - building and testing cameras, figuring out exposure times, testing photographic papers, learning to mix my own developer, and more. I arrived at the mill yard that first morning feeling nervous but reasonably prepared. Minutes into that first shoot, I realized the one thing I had not planned for - my vision required exposures measured in minutes in the face of constant movement. The solution turned out to be simple. I just had to embrace the movement. In the end, I found the resulting ghostly images of layers of trucks one upon the other satisfying and evocative - evocative of the frenzy of the harvest itself and the inexorable march of time.

I have mourned for the landscape of my youth, and I have at times resented the changes wrought by the passing years. My perspective was re-centered early one morning during the peak of the harvest. I had gotten to the mill before it opened and I had the opportunity to speak to a man from Mulberry, TX, a fourth-generation farmer of perhaps forty, who was waiting to be weighed. We had a nice chat about the good ole days, and about farming in the present. As our conversation drew to a close, he pointed out that despite the sweeping changes in farm technology, farm economics, and farming practices, “you still have to get it in the ground”. In that moment, I realized that things are not so different after all. For the men and women in the fields, the art of farming is still a profound act of communion with Mother Nature.

The author at home.

A hearty, "Thank you!", to everyone who supported me and tolerated my presence during the busiest time of their year.

If you were involved in this harvest; if you remember harvests of times past; if you grew up in the area, and feel some of the same nostalgia for the old days that I feel, I hope you will use the comments section to add your stories and your photos.